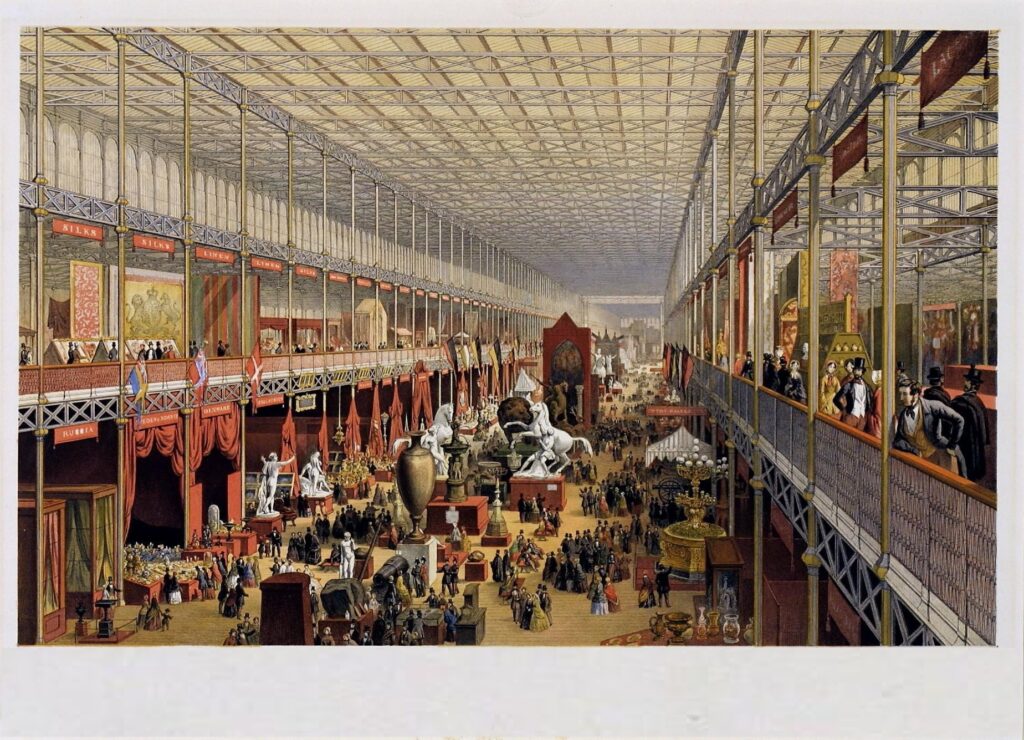

The Great Exhibition of 1851 stands as one of the most remarkable spectacles in the history of modern civilization. Held in London’s Hyde Park from May 1st to October 15th, 1851, it was the first international exhibition of manufactured products—an event that not only celebrated the incredible advances of the Industrial Revolution but also helped shape the idea of global expositions that continued for more than a century. By drawing together innovations, curiosities, and artworks from across the world, the Exhibition cast a spotlight on the achievements of the Victorian age and set new standards for cultural events.

Origins and Vision

The Exhibition emerged from the ambitions of forward-thinking Victorians, none more influential than Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, and Henry Cole, a pioneering civil servant. Inspired by the idea of international industrial exhibitions in France and Germany, Albert and Cole envisioned a grand event that would promote British industry, foster international cooperation, and showcase the latest advances in technology and art. Their vision was keenly imperial: to demonstrate Britain’s ascendancy as the workshop of the world while inviting other countries to participate and compete.

The project’s scope was unprecedented. The organizers had to convince parliament, the press, and the public of its value, raise funds, and select a site. The chosen venue, Hyde Park, would soon be transformed by engineering ingenuity.

The Crystal Palace: An Architectural Marvel

A contest for the design of the exhibition’s structure led to the selection of Joseph Paxton’s plans. The so-called “Crystal Palace” was a vast construction of cast-iron and glass, measuring over 1,851 feet in length (in honor of the year), encompassing more than 92,000 square meters—large enough to house mature trees and an 8-meter tall glass fountain within its dazzling halls.

Paxton’s swiftly-erected masterpiece required more than 2,000 workers and just nine months to complete. With sunlight streaming through its walls and roof, the Palace was a fitting home for the treasures it would contain. Its innovative techniques influenced architecture for decades to come.

India’s Prominent Role

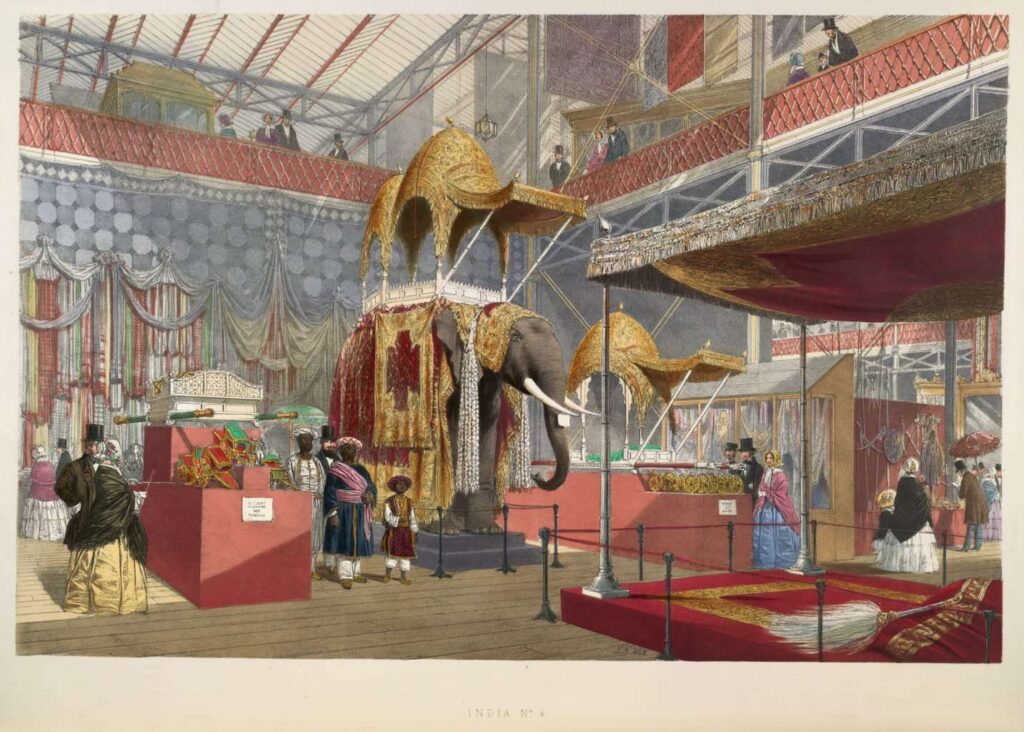

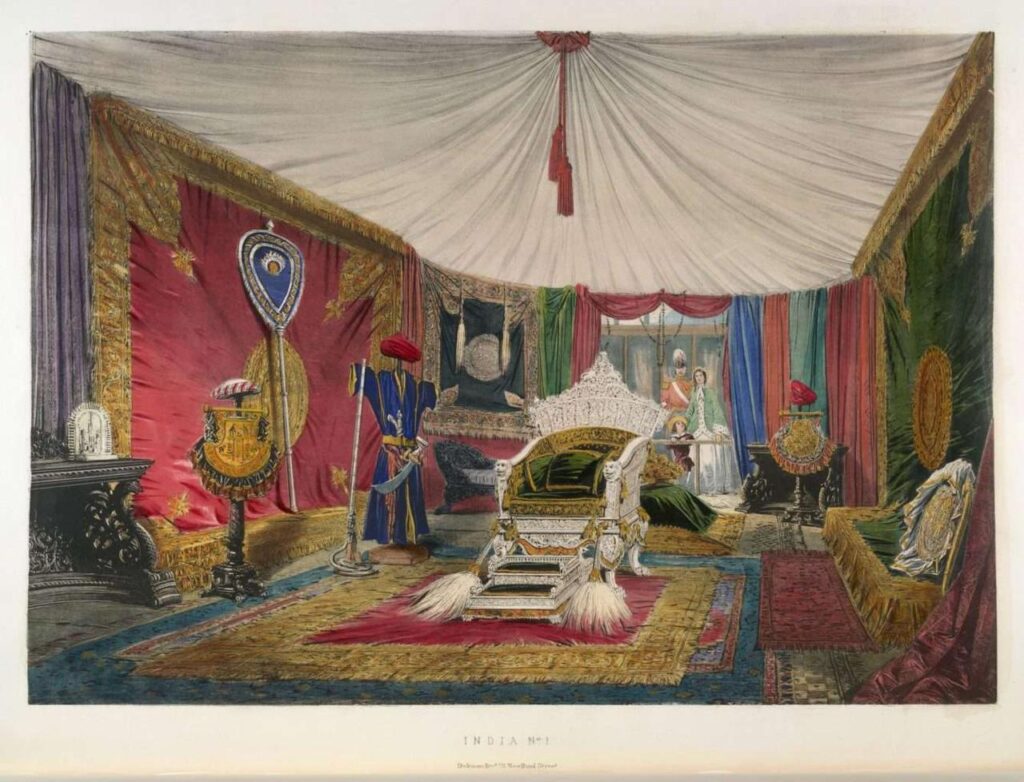

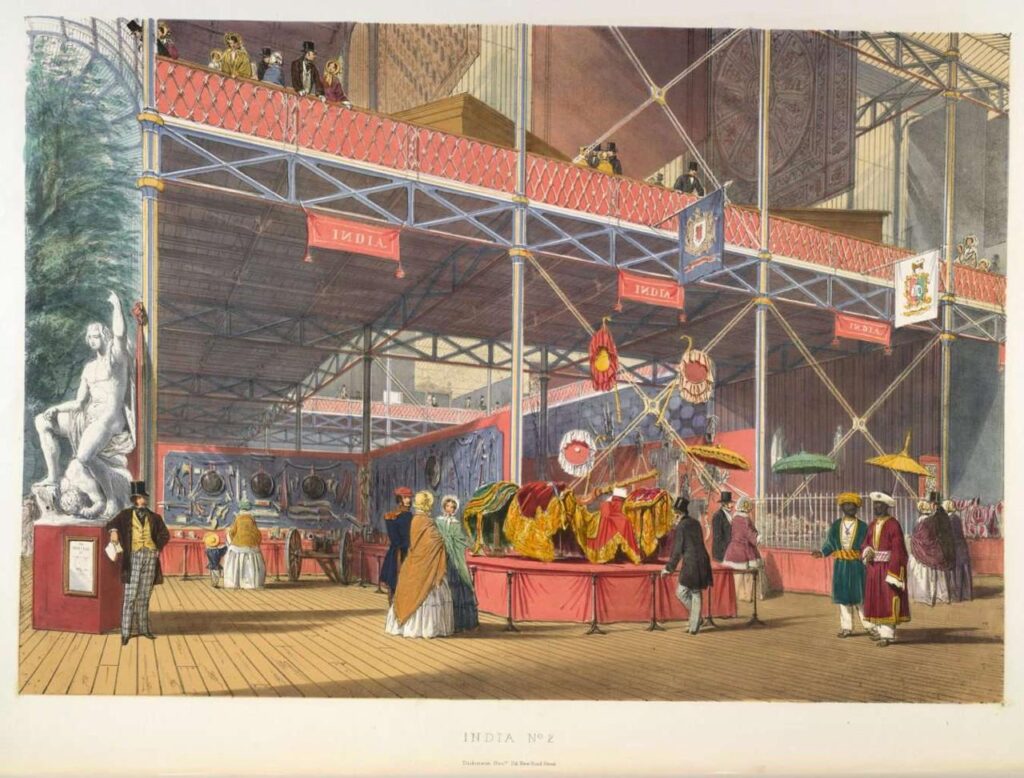

India was allocated approximately 30,000 square feet of exhibition space—significantly larger than other colonies and rivals. This colossal area underscored the importance Britain placed on India as a source of wealth, raw materials, and exotic goods. The Indian section in great exhibition was administrated by John Forbes Royle, a British botanist with decades of experience in India, who curated the displays to highlight India’s economic and artistic contributions.

Magnificent Exhibits

The Indian exhibits encompassed a remarkable variety of objects, vividly illustrating the diversity and sophistication of Indian craftsmanship. Visitors marveled at silks, jewelry, textiles, and precious gems, including the world-famous Koh-i-Noor diamond—the largest known diamond at the time—which embodied the imperial narrative of conquest and splendor.

Visitors could also see:

- A richly decorated stuffed elephant with a magnificent howdah, symbolizing the opulence of Indian royalty.

- Exquisite textiles, including Banarasi brocades renowned for their intricate gold-thread weaving.

- Raw materials such as cotton, wool, ivory, steel, and horn, showcasing India’s natural wealth.

- A detailed model depicting a revenue collector visiting a village, highlighting colonial administration and control.

The Story of the Banarasi Brocades

Among the many exceptional textiles displayed, the Banarasi brocades were notable for their artistry and cultural significance. Typically, Indian works were catalogued under generic titles like “productions of Benares,” which erased the identities of the skilled artisans behind them.

However, one particular brocade was an exception—it carried rare inscriptions naming Mu’in Lal, the trader who promoted Banaras’s goods on the world stage, and Budhu of Rasulpur, the weaver who wove his authorship into the gold thread itself. This brocade stands today as a testament to the pride, craftsmanship, and quiet defiance of Indian artisans under colonial rule. It is now preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where it continues to tell the story of Banaras’s rich textile heritage.

India as a Colonial Construct

While India’s presence at the Exhibition was impressive, it was deeply embedded within the colonial framework. The exhibits emphasized India’s role as a supplier of raw materials and traditional handicrafts, underscoring British narratives of progress and control. The Exhibition’s arrangement reflected imperial ideologies that portrayed India as a land of ancient, exotic tradition rather than modern industrial innovation. This presentation justified Britain’s colonial rule as a civilizing mission while framing India’s contributions within a British-centric global order.

Impact and Legacy

The Great Exhibition of 1851 cemented many ideas about India in the British and international imagination—images of a land rich in jewels, luxurious textiles, and ornate craftsmanship. The artifacts exhibited formed the foundation of India’s collection in major London institutions like the Victoria and Albert Museum, influencing Western perceptions of Indian art and culture for generations.

At the same time, India’s displays highlighted the complexities of empire: while Indian artistry was admired and collected, the identities and agency of its makers were often obscured or appropriated. The inscriptions on the Banarasi brocade remain a rare and powerful reminder of the human stories behind these magnificent works.

Conclusion

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was a landmark moment that brought together industry, artistry, and global cultures under one roof, capturing both the promise of the Industrial Revolution and the complexities of empire. India’s participation highlighted this duality: its dazzling displays—from the Koh-i-Noor diamond to intricately woven brocades—celebrated the richness of its heritage, even as they reflected the power dynamics of British colonial rule. Together, these stories underscore the exhibition’s lasting impact, reminding us of the enduring contributions of Indian art and culture to global history, while also revealing the tensions and contradictions of the Victorian era.

Leave a Reply